In its latest press release dated 8 December 2023, entitled “Eel restocking: a false good idea“, Ethic Océan confines itself to a series of approximations and inaccuracies that have nothing whatsoever to do with the environmental ethics it intends to defend, to explain the subtitle of its press release “Eel protection measures that are costly and whose effectiveness is questionable to scientists….“.

We would like to reply here in a more precise and well-argued manner to show that restocking, or rather the transfer of glass eels, is an important and consistent measure in eel management plans in many European countries.

The eel restocking or eel translocation within their European range is not a recent measure.

Eel restocking is a measure included in EU Regulation 1100/2007 on the restoration of this species.

This is not a recent measure, and was widely implemented after the First World War. In the Bulletin Français de Pisciculture, Jean Le Clerc, chief inspector for water and forests, describes a number of glass eel transfer projects carried out by the Netherlands, Germany, Poland and Italy. In France, the Abbeville station in the North of France, and later the Nantes station on the Loire, distributed glass eels to ” compensate for the depletion of adult eels, which is not peculiar to France ” (quote from Leclerc 1930, BFP,19, January 1930).

A long-standing practice in line with the degradation and disappearance of the Eels' habitats in Europe

While one might question the need for such translocations at the beginning, or even in the first half of the 20th century, given the relatively good condition of aquatic environments and the fact that ecological continuity was still respected, at least in the lower reaches of rivers, this was no longer the case from the second half of the 20th century onwards.

These low-lying areas are vital for the development of glass eels and for the production of young eels, which will spread to various environments in the watershed or the neighbouring coastal zone to produce yellow and then silver eels.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the quantities of glass eels caught were such that many fisheries managers felt that if the resource was exploited too much (to make fish glue or to feed animals when the market for human consumption was saturated), it would eventually become scarce, hence the need to reseed certain areas where the density of eels seemed to be dwindling.

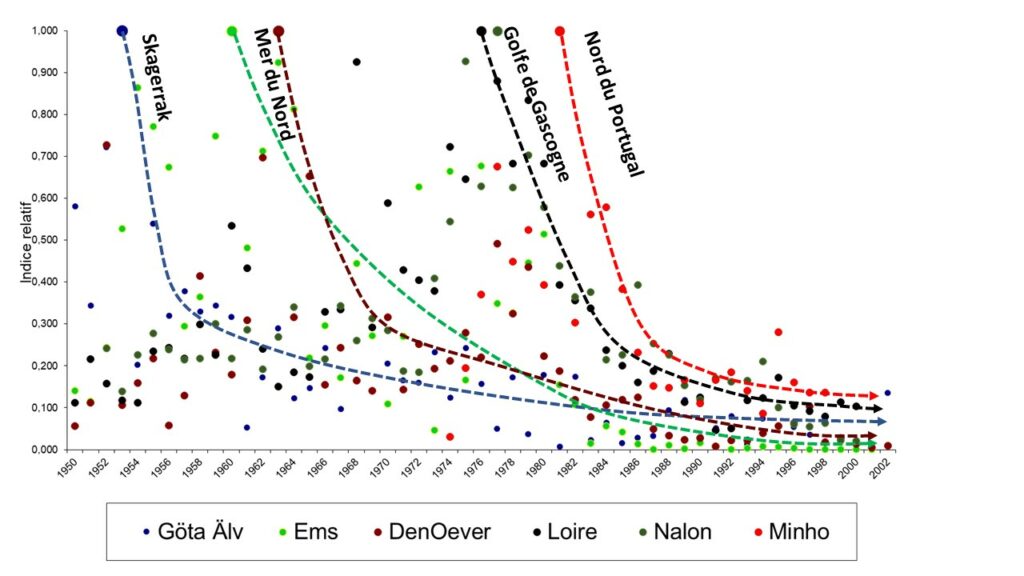

The species’ status changed dramatically at the end of the 20th century. At the beginning of the 21st century, nobody disputes the decline of the species in all the ecosystems it used to colonise, or the very significant drop in glass eel returns throughout its colonisation area, as shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 above shows that the decline in the colonisation of glass eels from leptocephali migrating from the Sargasso Sea began in the north of the range in the mid-50s (entrance to the Baltic Sea), then in the North Sea in the mid-60s and finally in the south from the late 70s (Bay of Biscay, north of Portugal), which remains the most irrigated area.

For the central part of the range, which corresponds to the Bay of Biscay, the decline in glass eel flows arriving in the main estuaries along the Atlantic coast can be traced back to the mid-1960s.

In 1994, the assessment report on wetlands showed that in France, more than half the wetlands had disappeared between 1940 and 1990. This was mainly due to sectoral public policies in the domains of agriculture, water reclamation and draining.

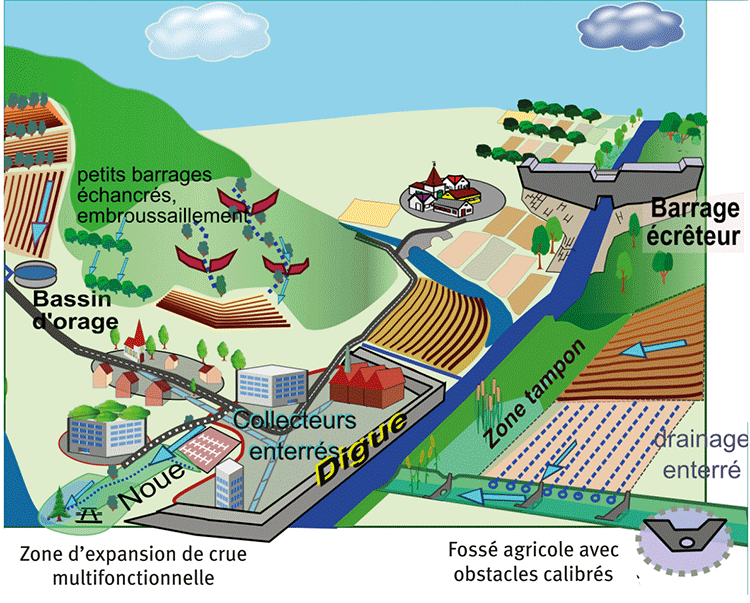

Over the course of the 20th century, the artificialisation of estuaries has progressively taken place: deepening of estuaries, development of port structures and logistics platforms, urbanisation of riverbanks, motorway development, etc. …. This has affected all the major estuaries along the Atlantic coast and the English Channel: Seine, Loire, Gironde, but also smaller estuaries such as the Charente and Adour. Shoreline areas have been filled in.

Although the environmental component of estuaries has been taken into account since the 1970s, the damage has been done and the artificialisation of estuary corridors has also affected the lower reaches of rivers to protect against flooding. Dykes, watertight flap gates and flood control dams have greatly reduced the carrying capacity of these environments, which are the main nursery grounds for eels. This has had an impact on the survival of juvenile eels, as is the case for many fish species which, like eels, need a territory to grow in good conditions.

At the same time, water quality has deteriorated. Over the course of the 20th century, we went from essentially organic pollution to biological and chemical pollution. PCBs, toxic products that accumulate strongly in the fatty tissues of eels, have been impacting aquatic environments since 1930. They were banned in 1980, but not by France until 1987. More recently, flame retardants and numerous medicinal products are contaminating the environment and causing physiological changes in many fish species.

The deterioration of inland aquatic environments has a considerable impact on the coastal zone. Over 80% of the pollution affecting the coastal zone comes from the land. Establishing a Marine Protected Area along the coast without addressing this problem is either a sign of incompetence or wishful thinking.

Thus, the transfer of a small part of glass eels from the best irrigated central zone and coming from degraded ecosystems to more northerly zones chosen according to precise criteria to optimise carrying capacity makes sense on the scale of the eel’s distribution area. This constitutes an active population restoration process, especially as in some ecosystems in the central zone there are signs of saturation of the host environment with existing glass eel flows.

"Scientists question effectiveness"

“According to scientists, these (restocking) operations have not proved their efficiency: the majority of glass eels released do not survive. In their latest opinion, ICES experts recommend that no catches should be authorised in 2024 – including for restocking“, says Ethic Océan in its press release.

Once again, so many approximations, shortcuts and distorted truths.

First of all, the latest ICES advice in 2023 (WGEEL report, Vol 5, Issue 98) makes no reference to restocking. It remains in line with the 2022 report and will continue to do so in the coming years. This makes its contribution completely useless, since, by virtue of ICES’s precautionary approach and the impossibility of assessing this resource and the impact of fishing on it, it confines itself to “advising” that no catches should be made, whatever their use.

In fact, two reports are important in laying the bases for restocking in France and Europe:

The first is published by GRISAM (Groupement d’Intérêt Scientifique sur les Poissons AMphihalins), which was published in 2015 and reviews the first 3 years of restocking in France over the 2011-2013 period, during which 20 million individuals were stocked for a total budget (including monitoring) of €4 million.

Three considerations emerge from this report:

1 – The actions from capture to release must be well controlled (non-traumatic fishing, storage in tanks as soon as the fish are caught, transport using appropriate means) and the release site must be carefully considered (high carrying capacity for young stages close to habitats that are favourable for growth).

2 – the survival of individuals is strongly linked to the quality of the individuals released, hence the need to develop good fishing practices. This is in line with the initiative subsequently taken by professional fishermen to publish, with WWF France, a guide to good practices and a charter of good practices for glass eel fishing. This charter must be signed by every owner of a glass eel licence. Recent results on glass eel quality show that this has led to a significant reduction in post-fishing mortality for all the gears used.

3 – Need to increase knowledge about the numbers of silver eels produced and their ability to migrate to the Sargasso Sea. This requires a better estimate of the natural mortality of young eels, which is currently estimated to be 90% from glass eel to small eel.

The Call for Projects document from the Office Français de Biodiversité (OFB) is based largely on this report and sets out both the health analyses to be carried out before any release and the release procedure (choice of site, density per hectare).

The second document is the June 2016 WKSTOCKEELreport published by ICES.

It defines what is meant by the net benefit of restocking (or transfer) from the donor ecosystem to the recipient ecosystem: “where the stocking results in a higher silver eel escapement biomass than would have occurred had not been removed from its natural habitat (donor) in the first place“.

It shows that the transferred eels contribute to local production of yellow and silver eels. The benefit obtained for the stock on a wider scale of investigation and the contribution of these transfers to the reproduction of the species cannot be quantified due to a lack of sufficient knowledge about the spawning population and the spawning process itself.

To better estimate this net benefit, research needs to be carried out on the carrying capacity of the donor ecosystem (studies show that it could be saturated with the current glass eel migration), the natural mortality of eels at different stages of the biological cycle and in different ecosystems, and the mortality of eels traded within the restocking network.

The answers to some of these questions are becoming clearer as a result of a number of recent studies on improving fishing practices and the storage and transport of glass eels used for restocking; on the survival of transplanted individuals; on the effects and impacts of density-dependency; on the comparison of the characteristics of transplanted and resident populations; and on the choice of release environments.

For example, the synthesis report coordinated by ARA France and written under the authority of the MNHN (Professor Eric Feunteun).

Projet-ADRAF-Analyse-des-Donnees-Repeuplement-Anguille-France-VF.pdf (repeuplementanguille.fr)

This report, which analyses the results obtained over a 10-year period of glass eel transfers in France involving 87 million individuals introduced into under-populated ecosystems, shows that this transfer is an effective measure for producing yellow and silver eels in habitats that are not or only slightly colonised by eels, and which show growth rates that increase the further away from the river mouth you are. This information will enable us to better study the impact of density-dependency processes and to better select the areas where transferred glass eels are released.

As we can see, the research teams, professional fishermen and all those involved in the eel industry in Europe do not limit themselves to “questioning” the validity of such transfers. They are investigating the effectiveness of the active restoration tool of restocking and are not saying that “these operations have not proved their worth: the majority of glass eels released do not survive” (according to CP Ethic Océan).

"These actions cost a lot of money and are used to financially compensate fishermen".

“These restocking activities in France are funded by the government to the amount of 2 million euros per year. This sum is used to compensate the fishermen who cannot market these glass eels: the State pays them 350 euros per kg“, Ethic Océan tells us.

The amount mentioned by Ethic Océan is taken from the call for tenders issued by the Office Français de Biodiversité, but does not just cover the purchase of glass eels. It takes into account the purchase, transport, release, health assessment, marking and monitoring surveys for restocking: growth, survival and dispersal of transferred individuals.

The protocol is detailed here

https://anguilleresponsable.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/20200603_AAP-repeuplement_2021.pdf

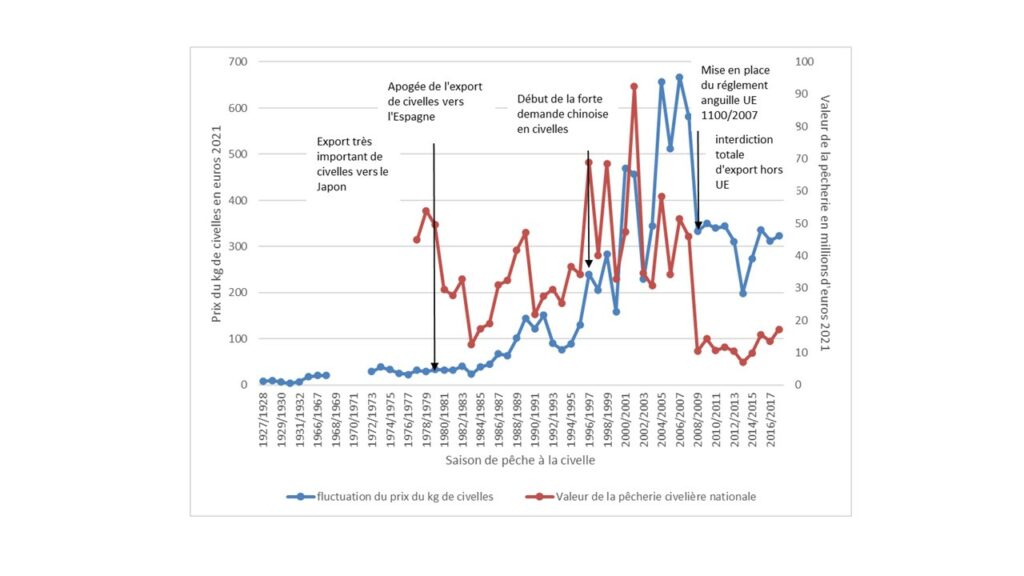

The sum paid to fishermen is not an indemnity, but a purchase made from the French restocking quota, a purchase also made by other countries for their restocking programmes as provided for in their national management plans. The sum of 350 euros per kg includes the fisherman’s purchase price, the wholesaler’s margin and the cost of organising the release. It is considerably lower than the price granted by the eel industry for the consumption quota (for the 2020/2021 season: 207 euros per kg of restocking glass eels compared with 363 euros for consumption).

It is true that it is not reasonable for this sum to be paid by the French taxpayer. These expenses should be paid by those who are responsible for the major impacts both on aquatic ecosystems and on the economic activity of those who depend directly on the productivity of aquatic ecosystems.

The polluter pays principle, adopted by the OECD in 1972 and incorporated into French environmental law by the Barnier Act of 1995, should be applied here.

For the moment, the only commercial activity that has paid the price is professional fishing, and particularly eel fishing, as shown in Figure 3 below. The value of this fishery fell by 1 to 5 after the introduction of Eel Regulation 1100/2007.

As for the fate of glass eels exported from France to other European countries, the statement “there is a very good chance that the glass eels will remain in the aquaculture farms of European countries to end up on our plates – and not to be released back into the rivers as planned” is the sole responsibility of Ethic Océan, but in the absence of proof, this is defamation and not environmental ethics.