Ignoring the Van-Ruyssen report (November 2023 P9_TA (2023)0411) calling for management plans to be implemented with a more global vision that takes better account of the many sources of pressure on the species and its habitats, Mr Sinkevičius, the Commissioner for the Environment, Oceans and Fisheries, has once again put the blame on fishing, using as a basis for his decision an ICES report whose main indicator of the evolution of the European eel population is based on the analysis of a highly biased trend in the estuarine recruitment of glass eels.

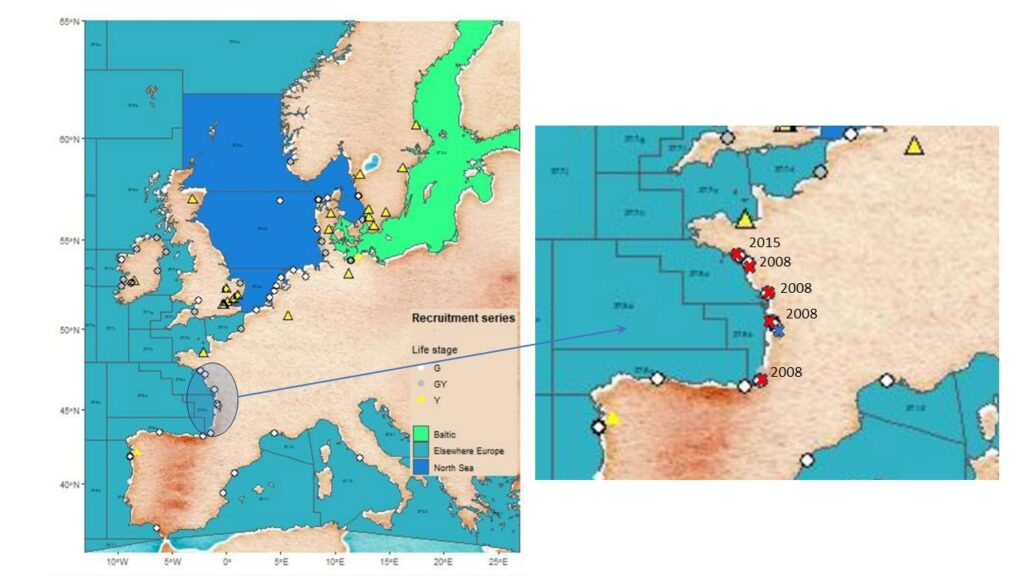

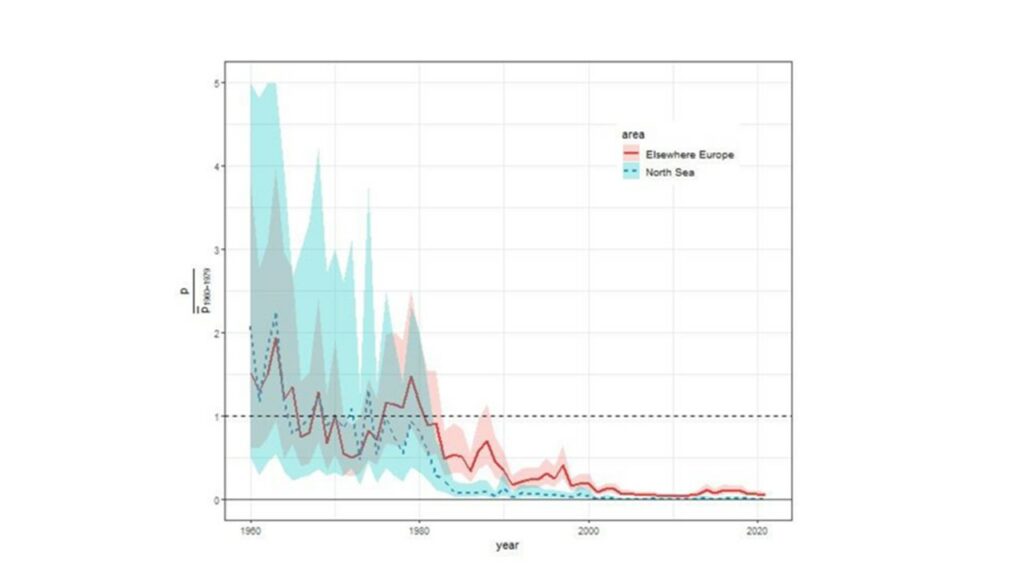

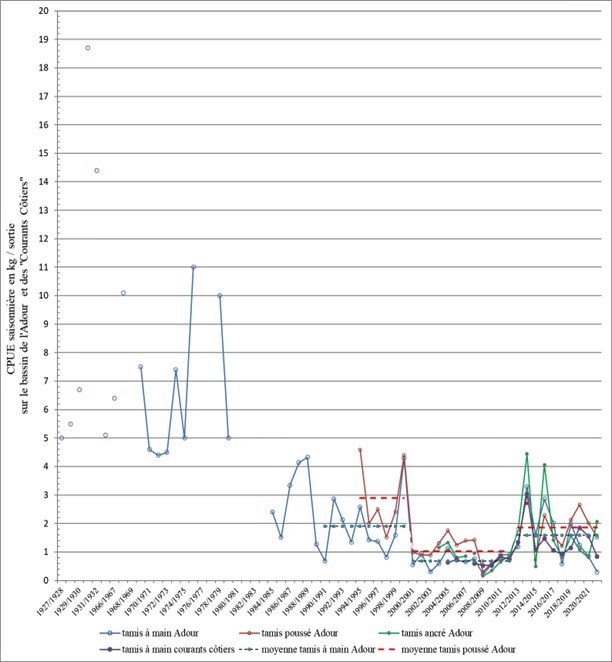

How can we pay attention to expert assessments of a resource based on a set of data that, since 2008, no longer even takes into account the fishing records collected by French professional fishermen, at the request of the authorities, in the main estuaries and catchment areas of the Bay of Biscay: Adour, Gironde and Loire (see Figure 1). Observations made on the distribution of the species show that this central part of the colonisation area is the most irrigated by the flow of glass eels from the waves of leptocephalus coming from the Sargasso Sea. This is where the constraints imposed on professional fishing in Europe since the introduction of Eel Regulation 1100/2007 will be felt first. It’s hardly surprising that experts who, contrary to the Principle of Prevention, do not use the best available data, can only faintly detect an improvement that is nonetheless being strongly felt with the existing series of data on the field. The figures below clearly show the difference in signal between the data series used by ICES (figure 2) and that provided by data series validated on the Adour and taken from fishing logbooks (figure 3).

How can we seriously detect a signal that should appear from 2013 onwards, when the most important series have been stopped since 2008. It is not surprising that ICES does not see that the increase in estuarine recruitment is significant, as Figure 3 below shows.

This approximate and narrow vision is a position all too often adopted by many so-called environmental NGOs who, in their desire to create a media buzz and clear their consciences, are only precipitating the impoverishment of these coastal, littoral, estuarine and continental resources, mainly through the degradation of their habitats by multiple uses.

Ethic Océan, whose aim is to preserve fish stocks and marine ecosystems, is a good example.

Its latest press release on eels is full of approximations and misunderstandings about the small fishing fleets that depend in part on the exploitation of eels, with no possibility of replacing them with other resources. This does nothing to protect the species or restore it.

As early as 1983, the European eel population in France (but much earlier in Northern Europe) was showing signs of depletion, observed and reported by professional fishermen. In 1993, a group of experts from the Groupe National Anguille set up the GRISAM (Groupe d’Intérêt Scientifique sur les Migrateurs Amphihalins) at the request of the French government. This group declared: “Eel fishing is a socially useful activity, but it is not the only factor responsible for the decline in stocks. Any source of mortality must be limited immediately if a recovery and restoration plan is to have any meaning. GRISAM fully shares the scientific position (and that of professional fishermen) that the eel is in danger”. This diagnosis was taken up by the ICES Eel Working Group until 2021: all mortality factors must be taken into account, not just fishing. After 2021, ICES changed the form of its advice, without unfortunately improving it, by focusing solely on fishing, as it does for purely marine fish resources. This new wording acknowledges that the data collected does not allow us to assess either the biomass of the stock or the indicators needed to define fishing quotas. Consequently, and in view of the significant decrease in the estuarine recruitment index since the 1970s, and in application of the ICES precautionary approach, the advice is that no catches should be made. This sectoral vision of the ICES can in no way resolve the problem of protecting this species, whose habitats have been severely degraded and its size greatly reduced. This is not the case, for example, with the species cited as an example by Ethic Océan: Atlantic bluefin tuna, a species whose habitat has not been reduced in size. This is absolutely not the case for eels, for which fishing regulation alone cannot achieve the objective set by the eel regulation 1100/2207: to reduce all the anthropogenic pressures exerted on this stock.

Since the introduction of the European Eel Regulation 1100/2007, fishing has largely achieved the objectives set for it, as demonstrated by the significant increase in estuarine recruitment. For uses other than fishing, few results have been obtained. Prefect Bernard’s 1994 report on wetlands, supplemented by subsequent reports on wetlands, the Senate’s report on water purification (Emmanuelli Report, 2003) and the National Assembly’s report on ecological continuity (Report 3425, 2016), show that not enough has been done.

More widely in Europe, the EEA’s 2018 report and the failure to achieve the objectives of the WFD, DCSMM and D/Habitats, which are constantly being postponed, also show that the areas in which these small-scale coastal, inshore, estuarine and continental fisheries operate have been degraded in a climate of general disregard. The short film below taken on the Loire by a professional fisherman in Nantes perfectly illustrates this attitude of indifference.

In this film, waste water comes out of a damaged pipe that normally flows to the bottom of the Loire in the centre of Nantes for all to see.

We would like to say to the members of the Commission that small-scale continental, estuarine and coastal fishing has been suffering for too many years from the errors of our policy to protect our aquatic environments: green tides, organic and chemical pollution, fragmentation of aquatic ecosystems, damming up of our estuaries, disappearance of riverbanks, impoverishment of our foreshore and proliferation of toxic algae, which is jeopardising part of our seaside economy.

It’s important not to forget that, for professional fishermen like oyster and fish farmers, water – whether marine, brackish or fresh – is a source of life and not just a liquid used to produce energy, dilute pollution, irrigate crops or quench our thirst.

To these great chefs from the Relais et Châteaux supporting the press release of Ethic Ocean and in particular to Mr Roellinger, eel fishing is essential to the survival of these small-scale fishing enterprises that land local, high-quality fish and contribute to the gastronomic culture of our territories. Without eels, most of them will disappear and with them a community of responsible fishermen who are fighting for better protection of these environments.

To Mr Gilles Bœuf, President of Ethic Océan, who used to be an councillor at the Ministry of the Environment and who should know that this Ministry is very often the adjustment variable for our national budgets. France, like Europe, has failed to protect the natural environments whose diversity we will need to adapt to climate change. This is what environmental NGOs need to be talking about, and not looking at the eel problem, as with many amphihaline species, through the prism of fishing alone.

If we want our ports to continue to be hubs of exchange, knowledge and know-how, and places where knowledge is transmitted rather than just boat garages, and if we want our rivers to be more than just water pipes, we must of course protect our marine, coastal, estuarine and continental aquatic environments, but we must also respect those who depend directly on them.