The information and observations gathered by our members in the field and in the fishmongers’ facilities undeniably show that the increase in the number of glass eels in our estuaries has been confirmed this year.

It is true that the large number of regulatory modifications defined, without consultation, by the European Commission and the multiple constraints imposed on the fishing industry make it more difficult to analyse long-term trends. However, all the qualitative and quantitative observations converge to indicate that the current abundance of glass eels in the French estuaries that flow into the Bay of Biscay is not only much higher than what was observed “at the bottom of the wave”, i.e. from 2000 to 2011, but, at least in terms of catches per trip, is comparable to what was recorded in the 1990s in various French estuaries.

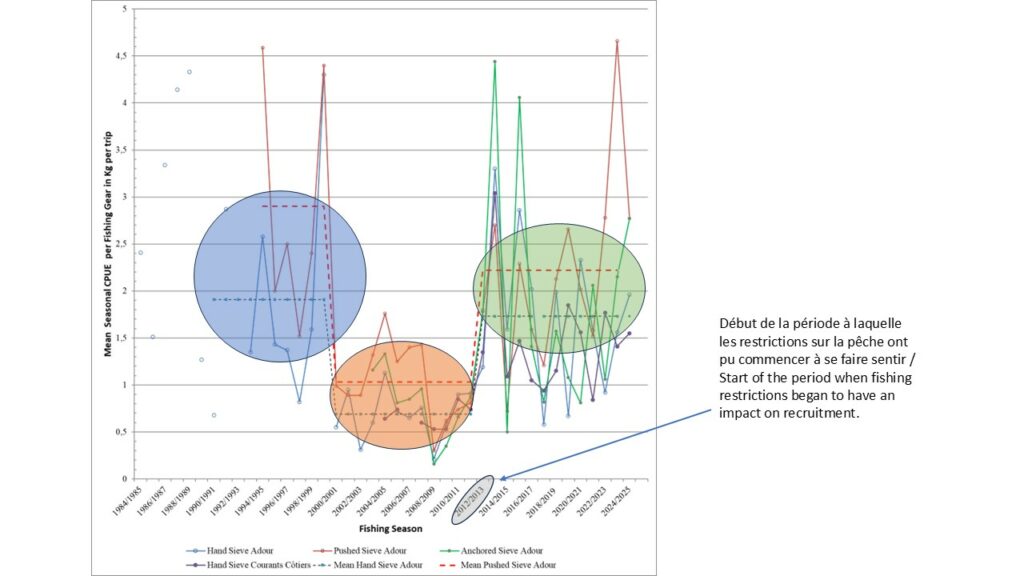

The graph above is based on fishing logbooks provided by fishermen in the Adour estuary over many years. These have been analysed by IFREMER, then by the CIDPEM64-40 in collaboration with professional fishermen. This is a valuable database that can undeniably serve as a reference for changes in the abundance of glass eel returns, at least in the southern Bay of Biscay.

Various observations can be made from this graph. Broadly speaking, several periods can be distinguished:

- The blue zone indicates the catches per trip (CPUE) made in the Nineties. The average CPUE is close to 3 kg per trip for the push sieve (2.9 kg), authorised in 1995 with two gears per boat. For the hand sieve, which is used with a single device, the CPUE is close to 2kg (1.91kg).

- In the red zone, a period of very low glass eel returns has been observed from the 2001 to 2011 fishing seasons. The use of the push sieve yields a single kg per trip (1.03 kg) on average during the fishing seasons. With the hand sieve, seasonal CPUEs are very low on average: 0.69 kg per trip during this period.

- From 2012 onwards, the restrictions imposed by EU Regulation 1100/2007 requiring a reduction in fishing effort of at least 50% will begin to have an effect. It is possible that other factors may have played a part, notably on the migrations of leptocephali during their transatlantic migrations, but what is certain is that fishing is the only anthropogenic factor to have achieved the objective set by EU regulation 1100/2007. Whether in terms of ecological continuity, environmental quality or reclaiming habitats that are still potentially available, efforts have fallen short of the targets set by the regulation. The latest period, from 2012 to 2025, is characterised by seasonal CPUEs that have more than doubled, on average, for both the push sieve (2.22 kg) and the hand sieve (1.73 kg) compared with the previous period. For hand sieves, the seasonal CPUE average is close to that observed in the 90s.

Within the different periods defined above, there are strong fluctuations in CPUEs, largely linked to the hydro-climatic variations encountered in the fishing area (in this case the lower and middle Adour estuary).

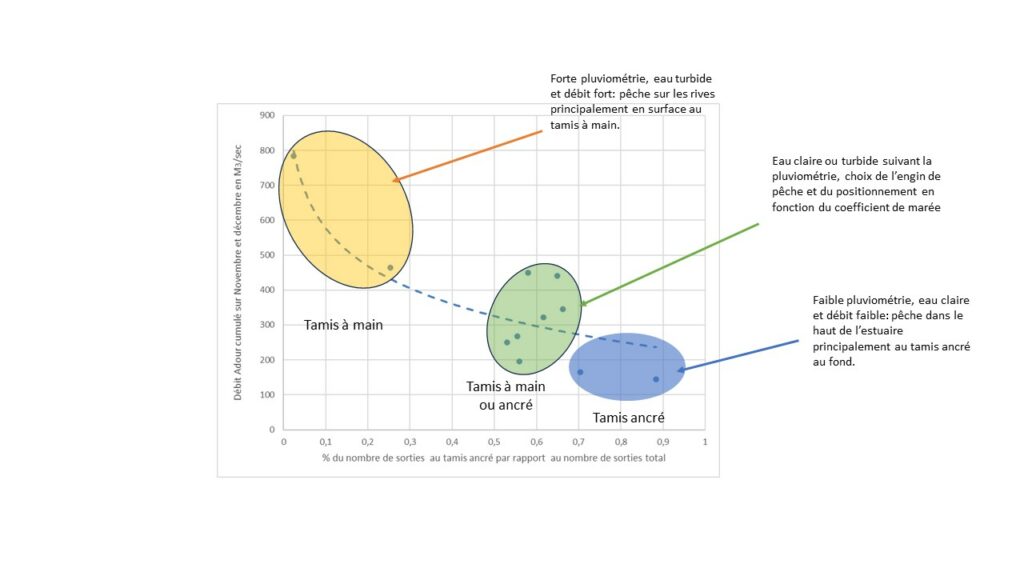

In the absence of heavy rain, the water in the Adour and Gaves estuary is clear. This means that the light can penetrate deep into the water column, which blocks the flow of glass eels at depth. Push sieves used without handles can only fish in the upper part of the water column, where glass eels are not present in great number. Under these conditions, the glass eel will move up close to the bottom, more or less quickly depending on the strength of the tide. In these conditions the use of the ‘anchored’ sieve is optimal, as it enables the flow of glass eels rising in the shallower waters of the upper estuary to be fished at the bottom. When the conditions are favourable: clear water, low flow and high tidal range, catches with an anchored sieve can be strong.

On the other hand, when the flow is very strong, the water is loaded and the glass eels, which cannot swim against the current in the estuary, are stuck on the surface against the banks and in the calm zones. In these conditions, the hand sieve can be used effectively and provide very good catches.

When the flow of the river is sustained and balances the force of the tide, the glass eels are partly on the surface and rise more slowly over the whole stretch of water. The push sieve is then the most appropriate device.

There are two types of professional fishermen in the Adour basin: marine and inland fishers. In the lower estuary, marine fishermen use push sieves, while in the middle estuary they use anchored sieves. In the middle and upper estuary, the inland fishermen use either hand sieves or anchored sieves.

The graph above highlights what has just been said. It also shows the very high level of knowledge among professional fishermen about the behaviour of glass eels (and, more generally, the biology of all migratory fish). This is a profession based on observation and traditional local knowledge, which is often transmitted from one generation to the next. It is becoming increasingly difficult to maintain this profession in estuaries and inland fishing areas. Yet these small-scale fishing communities offer invaluable help in assessing eel and migratory fish populations in environments where scientific equipment is not particularly well-adapted to the diversity of habitats.

It's not just in the Adour and Gaves basins that the situation is improving.

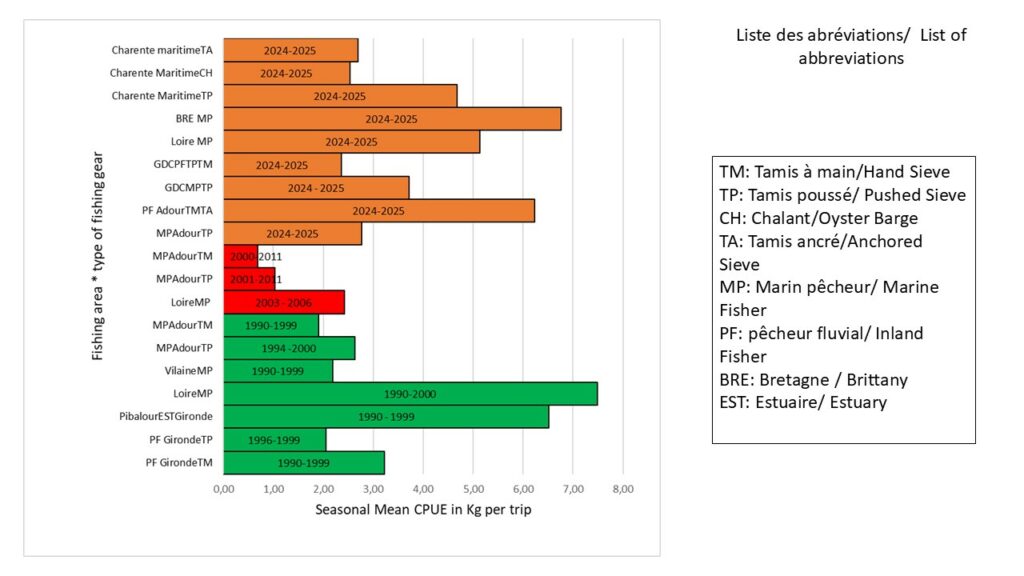

The graph above summarises historical data taken from various sources gathered in European eel projects.(Rapport final Contrat EC/DG FISH (DGXIV) N°99/023- Agreement 00/1213516/NF, rapport UE – IFREMER – LabSad-INSA – CEMAGREF – CSP, 147 pages + annexes, coord. P. Prouzet ; Rapport PECOSUDE, EC/DG FISH (DG XIV, 99/024 – Les Petites Pêches côtières et estuariennes françaises du Sud du golfe de Gascogne, Coord. J.-P. Léauté ; Prouzet et al, 2007. Quantification de la biomasse saisonnière de civelles (Anguilla anguilla) dans l’estuaire de la Loire et estimation du taux d’exploitation saisonnier de la pêche professionnelle pour les saisons de pêche 2003 à 2005. Rapport projet INDICANG,IFREMER-UPPA, 43 pages).

The period in green corresponds to information gathered in the 1990s on various estuaries: the Loire, Vilaine, Gironde and Adour, which are the main fisheries. Average catches per seasonal trip during the period shown for each fishing site are between 2 and 7.5 kg per trip.

The red colour covers the period from the early 2000s to 2011, the year in which the constraints on eel fishing introduced under Regulation 1100/2007 began to be felt. Data is available for both the Loire and Adour rivers, showing that average seasonal catches per trip are halved compared with the green period.

Finally, in orange, the current period shows that the seasonal averages of catches per trip are at the same level as those observed in the 90s, despite much greater constraints on fishing than in the 90s.

It seems clear that the increase in glass eel abundance in estuaries in the central part of the range is currently underestimated.

We don’t know whether this is intentional or not, but what we can say is that the conditions for applying the principle of precaution and the principle of prevention are not being fulfilled.

The precautionary principle involves assessing the risk engendered by a human activity on the eel population affected. This risk is clearly overestimated in the case of fishing and underestimated in the case of other anthropogenic factors. However, this improvement in glass eel returns can only be achieved in terms of yellow and silver eel production if ecological continuity is improved and the surface area of habitats actually available is greatly increased. This is not the case at present (see the national reports submitted to the ICES and the GFCM report). The Commission would do well to focus on achieving these last two objectives instead of lashing out at the fishing industry.

The principle of prevention is based on the use of the best available techniques and observations to minimise the occurrence of risk. This is not currently the case. The eel has been placed on the IUCN red list due to the sharp and rapid decline in glass eel returns since the 1980s. The European Commission, under pressure from a number of NGOs, has introduced stricter measures on fishing, on the grounds that the trend in glass eel returns shown by the curves used by the ICES, called North Sea and Elsewhere, does not indicate any significant increase.

This is not what we see in the ground and what we are currently recording (see § above). The Elsewhere curve, which is supposed to represent the fluctuation of glass eel runs in the central part of the range, is an aggregation of disparate data from the Atlantic coast and the Mediterranean, two areas where we know that the dynamics and intensity of glass eel arrivals in coastal areas are not the same. In addition, the most important data from the main French fisheries in the Bay of Biscay have not been taken into account since 2008, even though they are available.(see page 16 du Livre Blanc sur l’anguille – Un Livre Blanc sur l’Anguille Européenne signé par les structures officielles de la pêche professionnelle maritime et continentale en France – Anguille Responsable).

How can this “thermometer” be used to objectively measure an increase in glass eel returns, which we know will first appear in the estuaries of the Bay of Biscay? It is time for the European Commission to show a little more pragmatism and objectivity in its management of this species. The survival of small fishing communities depends on it, as does the restoration of the species.