The Oceans Summit currently taking place in Nice (France) within the framework of the United Nations talks in abundance about illegal fishing, plastic pollution and the preservation of certain “totemic” species. While these issues are important, they should not mask the lack of coherence of many management structures which, under pressure from certain NGOs, take decisions that are contrary to what has been democratically discussed and shared within participative forums bringing together elected representatives, scientists and users (see the 2006 eel workshop that led to the development of the European eel restoration plan).

The case of European eel management and, more broadly, the management of large migratory fish such as Atlantic salmon, shad and sea trout, is a perfect illustration of this technocratic

approach that flies in the face of what has been democratically discussed and decided, and which, under pressure from numerous environmental and non-environmental lobbies, ultimately fails to tackle the root causes of the problem. The management of these species boils down to applying the “Haro sur le baudet” procedure.

This means blaming the degradation of these fishery resources on an age-old activity which, for at least 40 years, has been constantly calling the public authorities to account for the deterioration in water quality, and the recklessness of those who use it as a lifeless resource, who artificialize ecosystems with high biodiversity and who pollute without taking into account the effects and impacts on the environment. All this has been denounced, proven and summarized in numerous parliamentary, senatorial and European reports.

The basis of European eel management is the EU regulation 1100/2007

Since September 18, 2007, this has included measures to restore the stock of European eel, enabling the long-term objective (duration not defined) of 40% of the quantity of eel that would have been produced in an environment unimpacted by human activity.

To achieve this, eel fishing at all life stages is not prohibited, but must be regulated.

More specifically, for glass eel, the mortality induced by its exploitation must be reduced by 50% compared to the estimated mortality from 2004 to 2008 ( considérant 14 du règlement). The achievement of this objective is measured in France by a scientific committee and reported annually to the French managing authorities. This fishing mortality reduction target is considered to have been achieved for the French glass eel fishery.

Objective (13): from July 2013, 60% of glass eels caught must be used for restocking projects (transfer from a donor environment to a receiving one). These projects are monitored annually. In France, this monitoring is coordinated by the Association ARA France, of which AFPMAR is a member, and carried out under the coordination of the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle.

“In the event of a significant drop in average market prices for eels under 12 cm in length intended for restocking,…., the Commission should be authorized to take the necessary measures, which may include a temporary reduction in the percentages of eels under 12 cm in length intended for restocking”. So what’s the Commission waiting for, if we refer to the previous news! see The restocking market is once again undermining the economy of the French glass eel fishery. – Anguille Responsable

The glass eel fishery has achieved its objectives in a responsible and transparent manner

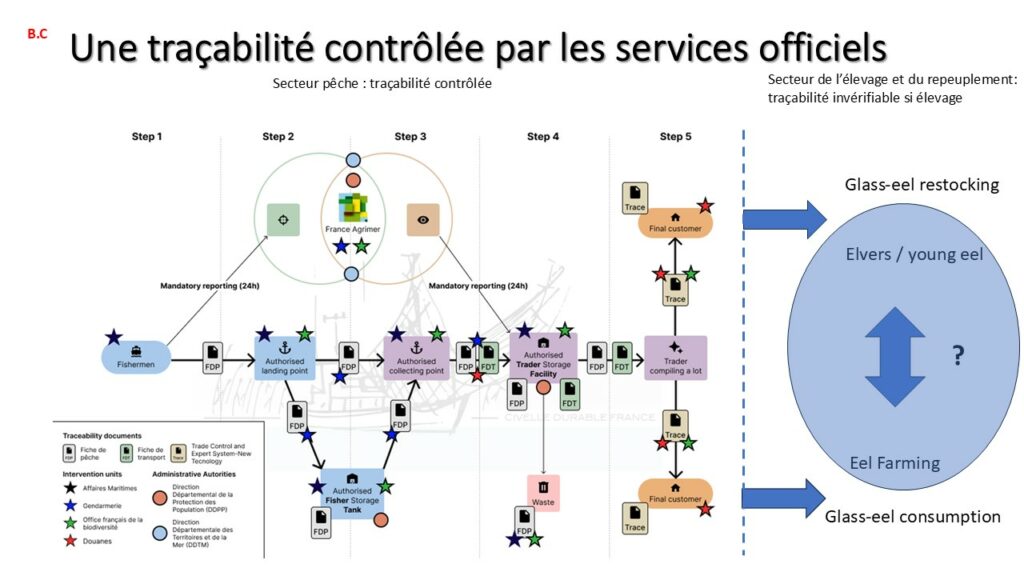

The fishing industry has achieved the objectives set by EU regulation 1100/2007. The traceability of catches throughout the fishing and fish-trading activity is strong and controlled by the various government services on the ground, from the catch to the end user. (see figure below)

We therefore fail to understand DG MARE’s and DG ENV’s determination to eradicate all eel fishing without any assessment of national management plans, and in the light of expert reports which admit their inability to assess the impact of pressure factors on this fishery resource (WKFEA 2021, 5.2.2. page 26). The enforcement of very short fishing periods in maritime areas is of little interest when management is based on quotas defined by a scientific committee whose members are involved in the expert assessments of the ICES eel working group. Whether the consumption quota is reached in 30 days or more, or whether the restocking quota is reached in 80 days or more, is of little consequence.

on the impact of the glass eel fishery on the eel stock, except to complicate the management and monitoring of the species with calendars that are not based on anything! (see news Another labyrinthine system under pressure from Brussels: fishing dates for glass eels! – Anguille Responsable)

DGMARE and DGENV’s questioning of ICES expert groups is irrelevant. The ICES eel working group has already replied that it was unable to assess this population given the observations collected and available. Since the introduction of regulation 1100/2007, no one has asked for management to be implemented within a classic framework of sustainable exploitation. The Van-Ruyssen report of 2023 made it clear that the Commission should focus on assessing the results of management plans and the minimization of all anthropogenic impacts, not just fishing.

A sluggish restocking market, due to the Commission's fault, under the control of the eel farming sector.

It is incomprehensible that the European Commission should refuse to apply article 7 § 6 of EU regulation 1100/2007 concerning the modification of the allocation key. Unless the Commission is arbitrarily doing so in order to favour the promoters of restocking in Europe, so that they can purchase glass eels at low prices in a context where supply far exceeds demand.

What we need to understand is that to reduce the restocking quota, we need to reduce the overall quota, which would automatically result in a sharp reduction in the consumption quota, which forms the basis of remuneration for the French glass eel fishing sector, as we saw in the previous news item.

As a result, the French glass eel fishing sector is one of the biggest financial contributors to restocking in Europe.

In fact, since France allocates a floor price of 260 euros for the purchase of glass eels under public funding, while the average price outside France for the 2024 – 2025 season is 149 euros, the deficit of over 110 euros generates a potential loss for the glass eel fishing sector estimated at nearly 3,111,000 euros, i.e. a forced contribution of 6,500 euros per fishing company.

This benefits restocking promoters, but does not increase demand for glass eels, as the farming sector is increasingly offering to supply eels whose traceability cannot be verified.

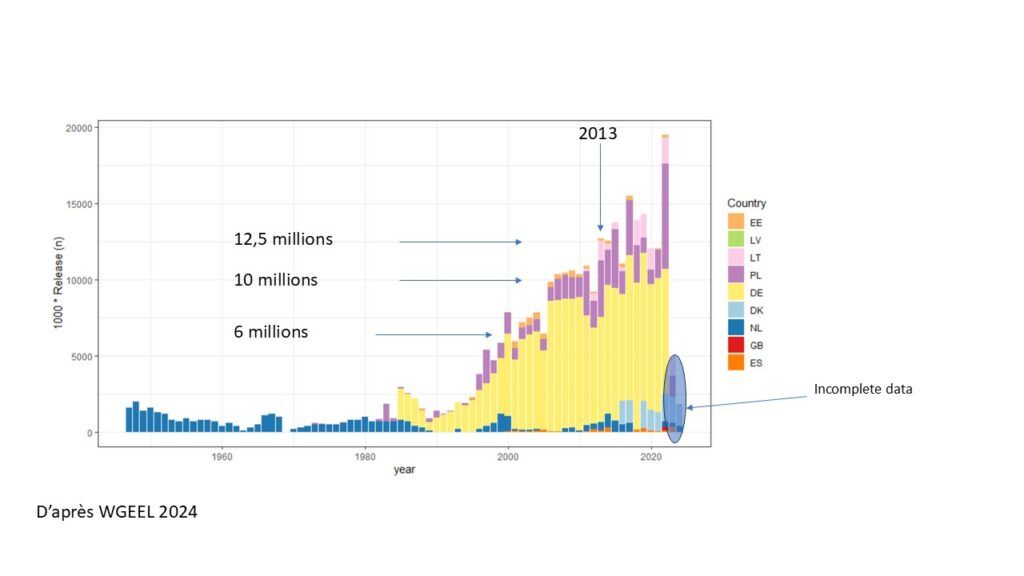

The graph above shows the increase in the release of farmed young eels in Europe.

Data for the last 3 years are not available, but there is good reason to believe that the use of farm-raised eels is set to increase.

This raises a number of problems, which we would like to highlight, given that restocking in Europe is largely financed by public and, in particular, European funds.

As far as biology is concerned, the few comparative studies show that good results can be obtained using glass eels or small farm-eels for yellow eel production in the wild, but there is no advantage in using small farm-eels instead of glass eels if restocking is done in spring (see Simon and Dörner 2013 – Survival and growth of E. eel stocked as glass and farm sourced eels in five lakes. Ecological of freshwater fish, vol 23, Issue 1, 40-48)

However, work remains to be done on the influence of the high-density rearing phase on the behavior of individuals released into the wild and on their sex ratio.

In addition, the risks of Herpes virus 1 infection of farm individuals are far from negligible, as some work shows (see – Kullman and Thiel, 2018 – Bigger is nbetter in eel stocking measures? Fisheries Research, Vol 205, 132 – 140). This is contrary to the recommendations of EU regulation 1100/2007, which insists on the sanitary quality of fish released to restore the species.

In terms of traceability, it is virtually impossible to know whether glass eels come from batches taken from the consumption quota or from the restocking quota once they enter the rearing phase. At present, no standard can guarantee this, whereas traceability is perfectly defined when glass eels are sold to eel farmers.

From an economic point of view, the production of young eels for restocking, which are sold for at least 5 times the price of glass eels, will lead to a reduction in demand for glass eels, estimated at 10 tonnes at European level, if public funding remains constant. (Note that this is the current deficit between French supply and European demand).

At the current price of 149 euros, this represents a financial loss for the French glass eel sector of 1,490,000 euros, to be added to the potential loss generated by a restocking market in Europe blocked, whether voluntarily or not, by the Commission.

This represents a total financial loss of 4,600,000 euros, or 9,200 euros in revenue per company for the 2024 -2025 fishing season. There’s good reason not to be happy about such an economic mess.