The European eel and its Environment

A bit of biology of this mysterious fish

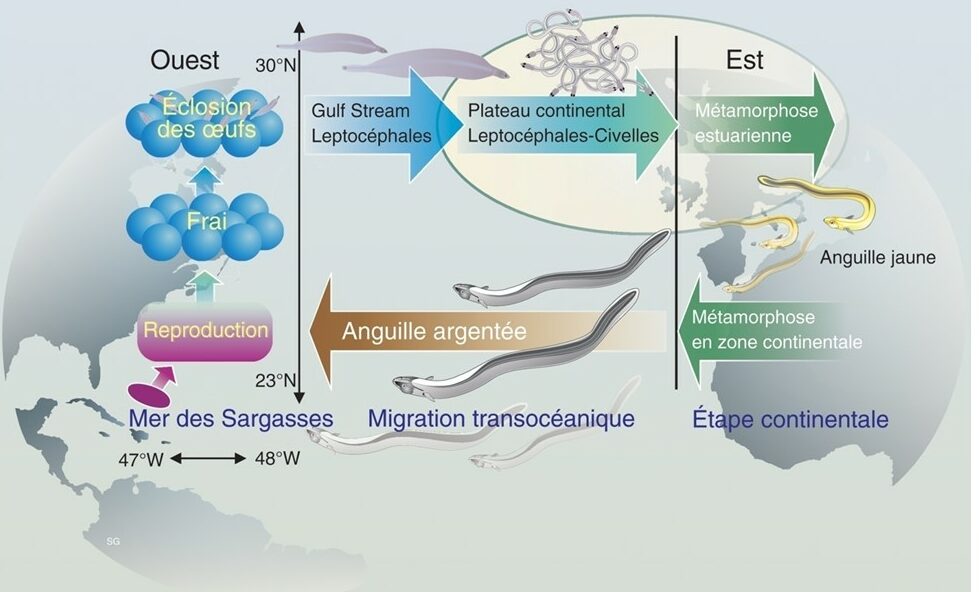

The European eel Anguilla anguilla is described as a catadromous fish: it goes to sea to reproduce. Eels reproduce at sea in an area that is believed to be located in or near the Sargasso Sea.

The larvae produced are called leptocephalus larvae and are carried by the Gulf Stream to the eastern North Atlantic and are distributed by different currents to the coastal areas between Mauritania and the northern Norwegian coast. On the continental shelf as they approach the African and European continents, the leaf-shaped larva develops into a small, cylindrical, transparent fish, which is called a glass eel or a “pibale” in the southwest part of France. The Anglo-Saxons call it a “glass eel” because the main vital organs of this small fish can be seen through the skin.

The glass eel then colonises the coasts, estuaries, bays and lagoons. Progressively, it becomes pigmented and gradually seeks to stay close to the sediment instead of swimming in the open water as it did previously. It is thus transformed into an eel, which is the stage of diffusion of the species in freshwater, brackish or salty environments, such as streams, rivers, ponds or lakes, estuaries, bays and lagoons. The growth period can last from 5 to 25 years depending on the growth rate: slower in the north of the range or depending on the sex of the eel: males are sexually earlier than females. At the end of this growth period, the yellow eel, on an autumn day, will transform into a silver eel to migrate to the sea at the first flood and thus ensure the survival of the species.

The European eel: an endangered species?

The European eel (Anguilla anguilla) is a robust species that inhabits a wide range of aquatic environments: coastal seas (such as the Baltic Sea), bays and shallow coastal waters (such as the Pertuis Charentais), coastal basins (such as the Arcachon basin), Mediterranean lagoons (such as the Gruissan or Thau lagoons), estuaries of coastal rivers (Adour, Gironde, Loire,. .), middle parts of rivers and lakes (e.g. Lake Grand-lieu).

While everyone agrees that this species has declined dramatically in many environments, it is an exaggerated claim, given the species’ dispersal and amazing plasticity, that it is on the verge of extinction.

Current observations are insufficient to confirm this and only concern certain environments accessible to scientific tools ( electrofishing for example). Long-term monitoring on a large scale only concerns the abundance of glass-eels or young eels that swim up the estuaries. These data have deteriorated considerably over the last 20 years due to the lack of resources allocated to the assessement of this species. Few observations and investigations are made in environments where the depth exceeds one metre. Little is known about abundance in coastal areas, estuaries and lakes, even though it is known that these environments can support large eel populations.

What we do know, however, is that the habitat that can be colonised by this species in Europe has been greatly reduced as a result of the determination of our societies to artificialise more and more natural areas: wetlands considered as second-class natural environments to be urbanised or cultivated; dyking of estuaries or rivers to protect against rising water levels; hindrance of ecological continuity by the construction of more and more dams and higher and higher dams with, and last but not the least, the explosion of species such as the wels catfish, which can live in increasingly warm and stagnant waters.

Yes, what we know for sure is that the areas available and accessible for eels have been reduced, and obviously the size of the population, but this in no way means that the species is on the verge of extinction, which is a very convenient excuse for calling for “the death of the fisherman”. This is an easy remedy, but it is more of a magic potion than a concerted reflection between the actors involved.

The only solution, and there are no others, is to reclaim the habitats that can still be reclaimed: rehabilitation of salt marshes, reconnection of wetlands (barthes, boires) with the river axes, facilitation of obstacle crossings by migratory passes and/or transfer of populations, transfer of populations to under-used areas (basis of restocking in Europe),…

Fishing activity: The root of all evil?

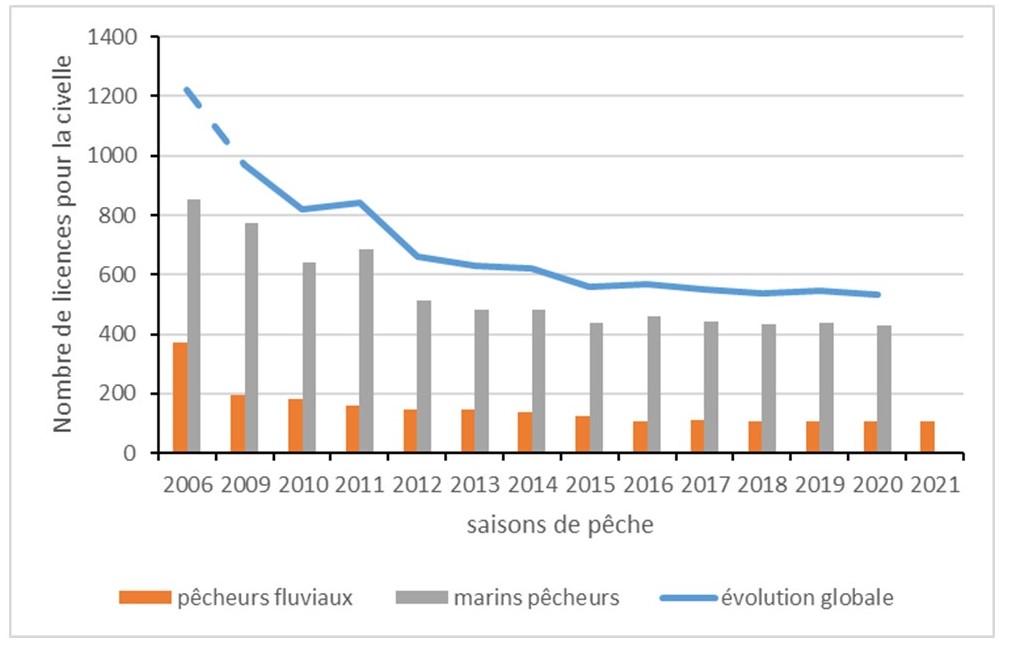

In less than 20 years (2005 to 2020), the number of professional eel fishermen has almost halved. Many watersheds are practically no longer exploited, not because there are no fish left, but because of increasingly strong administrative constraints that discourage many young people from taking up this profession. In the case of eels, these administrative constraints are compounded by pressure from recreational fishing authorities and certain NGOs that see small-scale inland and estuarine fishing as the source of all the problems.

However, the few observations made by scientists on the exploitation rates of the different life stages of the species: glass eel, yellow eel or silver eel, show that fishing is not the main mortality factor for the species.

One river basin sums up these comments perfectly: the Rhône basin, where professional eel fishing has been virtually non-existent since it was banned in 2009 (due to major pollution of the river’s sediments by PCBs). Fishing for glass-eels has always been banned in the Mediterranean Sea. Thus, for almost 15 years at least, professional exploitation of the species has been quasi non-existent in this basin and, according to the public authorities, the eel population is not recovering. Little has been done in this basin to improve ecological continuity and increase the size of the eel potential habitat, despite the continuous demands of the professional inland fishing industry, which did not want to sign the PLAGEPOMI (Management Plan for Migratory Fish), considering it insufficiently ambitious.

Many NGOs and recreational fishing associations are voicing their opposition to the massacre of glass eels in the lower reaches of the rivers on the Atlantic coast. As usual, their claims are not substantiated, despite the scientific information available in the scientific litterarure.

The European INDICANG programme (indicators of European eel colonisation in the central part of its range), in which the professional fishing organisations have participated, has shown that in large estuaries such as the Adour or the Loire, the exploitation rate of glass-eel is ranged according to fishing

(1999 – 2005) between 2 and 19%. The group of independent experts responsible for establishing the level of the French seasonal quota of glass eels to be caught showed that, on the whole, the exploitation rate had decreased compared to the reference period (2004 – 2008). If we take into account, as we should, only consumption, the decrease is of the order of 2, which means that, on the Atlantic coast, the rate of exploitation of glass-eels should be close to the level of 10%. This value should be compared with the natural mortality rate at this stage, which is between 80 and 90%. In pragmatic terms, this means that the impact of glass eel fishing on the mortality of young eels is at most around 2%, which is much lower than the impact of dams that block migration and the mortality caused by hydroelectricity production, for example.

Professional fishing is not a destructive activity. The analysis of national eel management plans by the European Union has shown that the fishin sector has achieved the objectives assigned to it in terms of reducing its ecological footprint. Those who consume eel should not feel guilty about supporting this industry in Europe, which contributes more than any other to the protection of aquatic environments through its environmental monitoring and restocking activities.