A Responsible Fishery

Responsible rather than Sustainable

Fishing is considered biologically sustainable when it removes a maximum number of individuals from a given fish stock equal to the maximum sustainable yield. In order to explain what sustainability means, it is important to go back to the definition of “Sustainable Development” and “Maximum Sustainable Yield”.

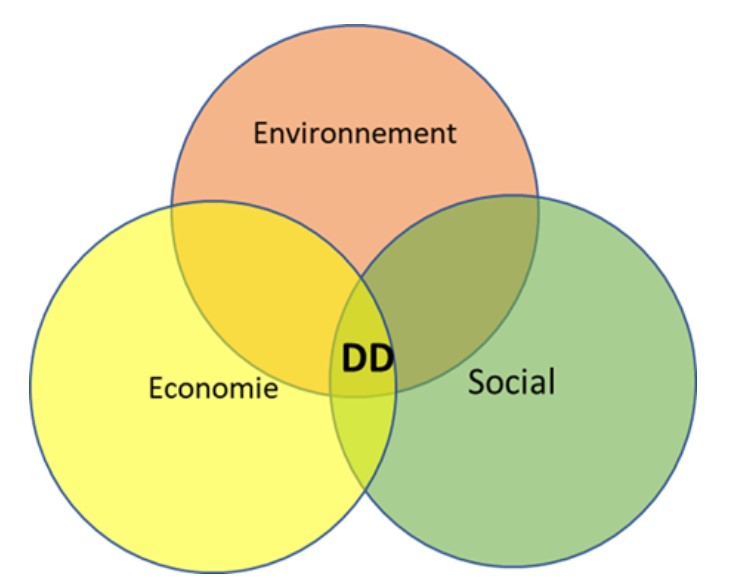

The concept of sustainable development (SD) is defined in the report “Our Common Future”, also called the Brundtland Report, published in 1987. According to this report, Sustainable Development lies at the convergence of three spheres of interest: economic, social and environmental, as shown in the figure below.

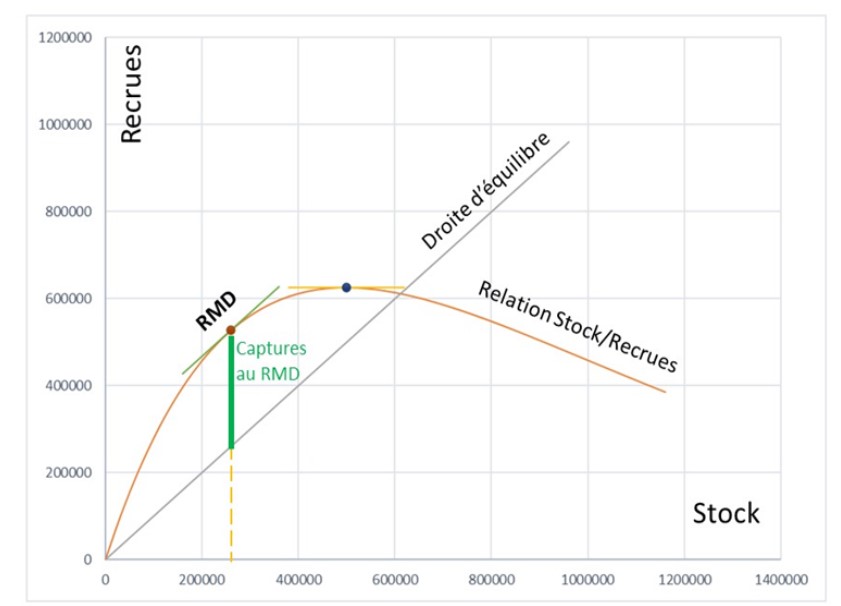

Maximum sustainable yield (MSY) is an indicator used in fisheries biology that theoretically allows us to know the maximum quantity that can be extracted from a fish resource without affecting its future abundance. In fisheries management, it allows, in a natural environment of given productivity, to better adjust the fishing pressure so that the exploited resource can be sustained at its best level. It is in fact what is known as the maximum interest (catches) that can be taken from the capital (fish stock) without it shrinking.

It is expressed graphically as follows:

Under these conditions, the fisherman ensures the sustainability of his activity by respecting the environmental dimension (resource maintained at its optimal level), the economic dimension (maximum and sustainable profit) and the social dimension (maintenance of the number of employments.

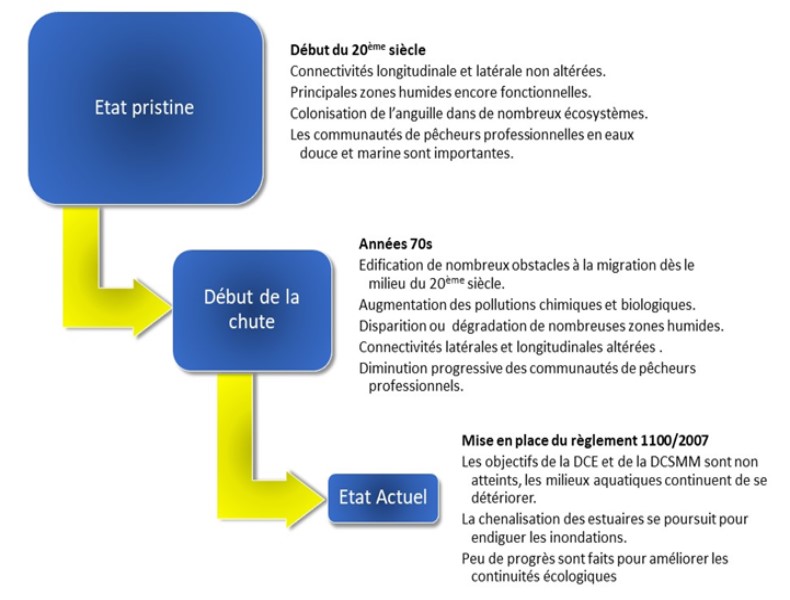

However, the situation is quite different, because while it can be accepted that the capital constituted by a purely marine fish resource (bluefin tuna, for example) is only affected by fishing activity, this is not the case for species such as the eel, a large part of whose cycle takes place in waters and environments that have been heavily impacted by human activities. These activities have greatly reduced the production areas of the species, either through the irreversible destruction of numerous wetlands or through the erection of barriers that have affected the ecological continuity of the catchment areas, which is essential for this species to colonise all its potential habitats. In this case, and compared to the middle of the last century, the size of this population is shrinking as a logical consequence of the reduction in the size of its accessible habitat; the surface area of this habitat determines the size of the population. It is easy to understand that in order to return to a more favourable previous state (not to mention the pristine state = origin), the regulation of fishing alone is an insufficient and far too sectorial measure which leads to useless sacrifices by part of our fishing communities and does not lead to the expected improvements.

Some figures: 90% of the eel’s original habitat has disappeared in Spain; 65% of Europe’s wetlands have disappeared or are degraded; 1,200 dams have been built in the Mediterranean basin, making it almost impossible for glass eels or young eels to migrate to their continental production habitats.